September 2021

Food allergy is a significant food safety concern requiring the identification and control of food allergens throughout the food supply chain. Food must be properly labelled to enable allergen avoidance when required, prevent reactions and protect public health. Food businesses will wish to provide food that is safe for consumers with allergies and avoid incidents and recalls. This Information Statement describes different manifestations of food allergy, symptoms, treatment and prevention strategies and current legislation which aims to protect the health of those at risk and support their quality of life. It provides guidance on controls to be implemented by food business operators to reduce the risk of unintended allergen exposure.

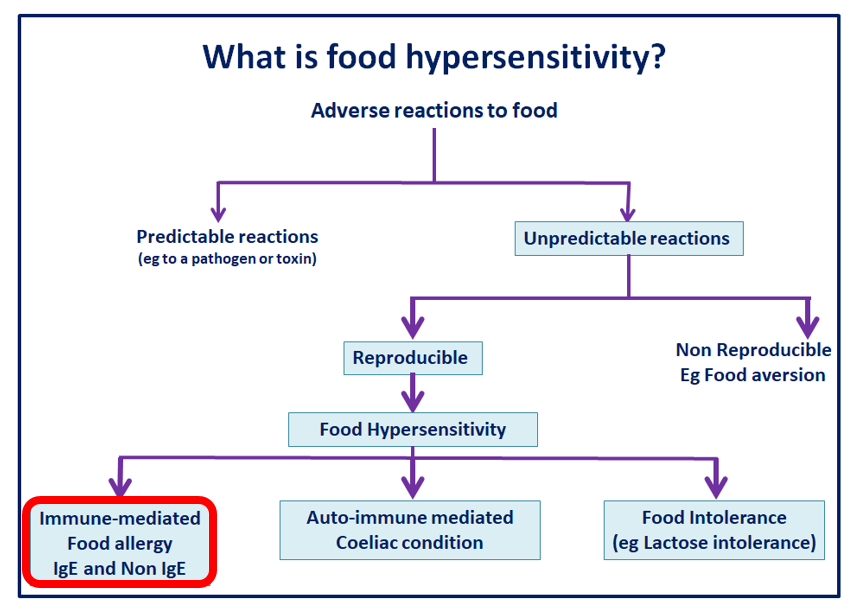

Food hypersensitivity is a term used to describe a sub-category of adverse reactions to food. Where reproducible symptoms follow contact with or (more usually) consumption of a particular food, which can be sub-classified as follows:

- immune-mediated food allergy – the focus of this IFST Information Statement

- coeliac disease – an auto-immune condition involving hypersensitivity to gluten

- food intolerance – symptoms elicited by the pharmacological effects of food components such as histamine, non-coeliac gluten sensitivity, enzyme and transport defects, such as lactose intolerance and some food additives e.g. tartrazine, annatto, sulphites, benzoic acid, and short chain fermentable carbohydrates e.g. fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs).

What is an immune-mediated food allergy?

It is estimated that approximately 1-2% of adults and 5-8% of children in the United Kingdom (UK) live with immune-mediated food allergy. This is classified according to whether the onset of symptoms is immediate (from a few minutes to about two hours from exposure or consumption of the food allergen) or delayed (from a few hours to days, or even longer after exposure or consumption). Immediate-onset food allergy involves an Immunoglobin E (IgE) antibody response, whilst delayed-onset food allergy involves different immune mechanisms. Some delayed-onset food allergy was previously described as food intolerance but is becoming increasingly better understood.

IgE mediated food allergies

The IgE mediated response is a two-step process:

- sensitisation

- elicitation.

Sensitisation can begin with the person being exposed to a food allergen by consumption, by inhalation or via the skin (particularly broken skin such as eczema). If predisposed to do so their body may respond by treating the allergen as a threat and make specific IgE antibodies against particular proteins (allergens) in the food. A similar mechanism is triggered for other allergens e.g. insect stings, animal dander, saliva or house dust mite.

Elicitation is the immune system trying to protect the body from a perceived attack. If a pre-sensitised person is exposed to the same allergen again e.g. by eating the food, it may bind with the specific IgE antibodies, and set off (or ‘elicit’) an allergic response. The binding event causes a release of histamine and other mediators that give rise to the symptoms of a systemic allergic response.

Further information about allergy is available at the British Society for Immunology website https://www.immunology.org/public-information/bitesized-immunology/immune-dysfunction/allergy

A useful database of food allergens can be found here: http://research.bmh.manchester.ac.uk/informAll/allergenic-foods

Allergic response symptoms

Most food allergic reactions are mild. Fluid released from blood vessels can cause swelling (angioedema), particularly of the face, mouth and throat. Localised swelling of the mouth and face, itching, rash/hives, (urticaria) runny eyes or nose, flushing, or clamminess of the skin are usually mild and may resolve with minimal or no medical treatment. Gastro-intestinal system symptoms e.g. nausea, pain, and vomiting may occur. With mild symptoms, it is prudent to bear in mind the possibility of progression to more serious illness.

Reactions which progress may often involve difficulty breathing due to swelling in the throat (larynx), or asthma. Cardio-vascular symptoms, faintness and dizziness due to compromised circulation, may lead to more severe cyanosis (not getting enough oxygen to the lungs) or cardiac arrest (inadequate circulation causing the heart to stop). Anaphylaxis is a term used to describe a more severe allergic reaction involving multiple organs, with the potential to become severe or life-threatening. 124 fatalities were assessed as being highly likely to be caused by ingestion of a food allergen, between 1992 and 2012, although misclassification might make the total somewhat higher. Hospitalisations for anaphylaxis increased between 1992 and 2012, but the incidence of fatal anaphylaxis did not. The age distribution of fatal anaphylaxis varies significantly according to the nature of the eliciting agent, which suggests a specific vulnerability to severe outcomes from food-induced allergic reactions in the second and third decades of life.[1]

Further information about anaphylaxis is available from the Anaphylaxis Campaign: https://www.anaphylaxis.org.uk/hcp/what-is-anaphylaxis/signs-and-symptoms/

Diagnosis and treatment

The diagnosis of IgE mediated allergy usually depends significantly on taking a careful history of reactions and symptoms, supported by skin prick testing using allergens in solution or ‘prick to prick’ using the real food. In some cases, IgE blood tests may be helpful. Some clinicians may arrange a food challenge, i.e. supervised consumption of the food allergen, to confirm the diagnosis.

Most mild allergic reactions to foods will resolve without treatment. In some cases, symptoms progress and have the potential to become severe or even life-threatening. Those known to be at risk may be prescribed adrenaline (epinephrine) auto-injectors. These provide a single measured dose of adrenaline injected into the thigh. Adrenaline acts quickly to constrict blood vessels, relax smooth muscles in the lungs to improve breathing, stimulate the heartbeat and reduce swelling around the face and lips. Repeat doses may be needed, so those known to be at risk are advised to carry two auto-injectors and to be ready to call emergency paramedics. Additional treatment may involve more adrenaline, replenishing circulatory fluids, oxygen, the use of asthma reliever medication, antihistamine and corticosteroids.

The mechanisms of food allergy are increasingly well understood. It is now easier for clinicians to work out exactly which food proteins somebody is allergic to, leading to more targeted advice about possible symptoms and treatment. There is, however, no cure for allergy, as yet.

Causes and prevention

There are still major knowledge gaps about why some children and adults become allergic to foods, but some aspects are increasingly understood. Atopic (allergic) disease can be inherited, and related manifestations (asthma, eczema, allergic rhinitis) are common in individuals with food allergy and their family members. Mutations in the filaggrin gene[2] are associated with dry skin, atopic eczema and an impaired skin barrier, which allows access to the immune system by food allergens and may be one of the sensitisation steps.

There is currently no evidence that maternal diet in pregnancy impacts whether a baby develops food allergy. Deliberate and regular consumption of common food allergens in early life (from 4 months of age) has been found to be protective in atopic babies. The immune system is less likely to be sensitised if the allergenic foods are regularly consumed, than from allergen exposure in the home/environment via an impaired skin barrier. There is more information about early dietary intervention to prevent allergy at:

- LEAP (Learning Early About Peanut): http://www.leapstudy.co.uk/

- EAT (Enquiring About Tolerance): https://www.food.gov.uk/research/food-allergy-and-intolerance-research/eat-study-early-introduction-of-allergenic-foods-to-induce-tolerance

Further guidance about weaning is available from Allergy UK:

https://www.allergyuk.org/assets/000/003/032/DesignConcept_A5_Info_Book_v1.5_original.pdf?1589795676

Can food allergy be treated?

Some food allergies are naturally outgrown in early life. Others may resolve by the introduction of individual food allergens (particularly milk and egg) to the diet in forms where some of the proteins have been broken down (denatured) by baking or cooking. Immunotherapy, a desensitisation process carried out under clinical supervision, may be helpful. Over weeks or months, the baby or child will be given foods in which the allergen proteins are increasingly intact e.g. by being less heat treated. Milk, for example, may be given first in a highly baked malted milk biscuit, gradually followed by different products and dishes leading to the introduction of fromage frais and fresh milk. Egg may be introduced in a muffin, then in baked or fried batter, and eventually scrambled or lightly boiled. Peanut has been introduced in measured and increasing amounts of peanut flour added to everyday foods. With appropriate clinical guidance, peanuts, tree nuts and other foods may be given in safe incremental doses in a pharmaceutical dosage form, such as capsules.[3]

Cross-reactive allergens

Cross-reactivity may exist between proteins which are similar in size or shape from different foods. Symptoms may be elicited when consuming a new food even if there has been no previous exposure to it. It is important to recognise the possibility of cross-reactivity when determining the cause of an allergic reaction. It may not have been caused by a particular allergen, through previous exposure, but by something with a structurally similar protein, which was able to elicit a similar adverse reaction.

Pollen-Food Syndrome (Oral Allergy Syndrome) is a common example of cross-reactivity. Individuals who are sensitised to tree or grass pollen may experience seasonal allergic rhinitis or hay fever. They may also have symptoms when eating foods which have proteins which are similar to these tree or grass pollen proteins. One of the most common cross-reactive pollens comes from birch trees and the most common trigger food allergens are: raw apple, kiwi, some nuts and other fruits. In most cases, symptoms involve immediate itching and swelling of the lips, mouth and soft palate, which are rarely life-threatening, and may resolve with a drink of water and/or an antihistamine tablet. Some reactions may become more severe, requiring the use of an adrenaline auto-injector. People with asthma may be advised to keep it well-controlled using preventer medication to mitigate symptoms

https://www.bda.uk.com/resource/food-facts-pollen-food-syndrome.html

Non-IgE mediated food allergies

A range of allergic conditions not associated with IgE mechanisms are briefly described in Appendix 1.

[1] Baseggio Conrado, A., Ierodiakonou, D., Gowland, M. H., Boyle, R. J. & Turner, P. J. Food anaphylaxis in the United Kingdom: Analysis of national data, 1998-2018. BMJ 372, 1–10 (2021).

[2] Irvine AD, McLean WI, Leung DY. Filaggrin mutations associated with skin and allergic diseases. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011 Oct 6;365(14):1315-27. https://www.eczema.org.au/dry-skin-and-the-filaggrin-gene/

[3] Anvari S, Anagnostou K. The Nuts and Bolts of Food Immunotherapy: The Future of Food Allergy. Children (Basel). 2018;5(4):47. Published 2018 Apr 4. doi:10.3390/children5040047

At its most basic level, an allergen risk assessment within food risk management procedures involves examining any product or dish to understand its composition and production, and thus the likelihood of allergen content. Consideration should then be given to finding out whether non-ingredient allergens are handled nearby, and whether there is any way in which they could get into the original product or dish. This involves examining the process and the character of the product or dish being made, the potential for unintended allergen presence, and the nature of any unintended allergen - whether liquid, powder, grain, chunks, pieces, fatty etc. Consideration should then be given to existing controls and ways to segregate, physical distance, scheduling production, covering or wrapping, washing and cleaning.

Assessing the potential allergenicity of foods and food contact materials

Allergenic foods of public health importance have been identified in the past, based upon reports in the literature of serious adverse allergic reactions. Research work, involving public health, risk assessment and risk management experts, has been done to confirm the criteria for determining whether a reported allergenic food is of public health importance. These include consideration of whether a food provokes severe reactions upon exposure to small amounts of the food and whether there is a significant prevalence of sensitivity to the food in the population[1],[2]. Regulators will then implement controls for major allergens of public health importance, such as mandatory labelling and expectations for allergen cross-contamination risk management, as part of Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) and risk management systems for food. Different regulatory jurisdictions have different mandatory allergen labelling lists because their local populations have allergies to different types of foods. There are foods however which people are commonly allergic to across the world and these are found in the Codex Alimentarius allergen labelling list[3]. A useful chart of the various different allergen labelling lists across different country jurisdictions is produced by the Food Allergy Research and Resources Program (FARRP) at the University of Nebraska, USA[4].

Potential allergenic risks, from genetically modified or novel foods, additives or food contact materials need to be assessed as part of risk assessment before these foods are permitted on the market. Recent examples involve developing ingredient isolates from wheat, whey or pea which may have different allergenicity from that food in standard form. Current and recent innovation, which has required such risk assessment, also includes the possibility of proteins from insects for human consumption causing allergy in people allergic to shellfish[5] and the use of non-plastic drinking straws coloured using a soya-based paint. In the European Union (EU), this work is undertaken by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)[6]. The Food Standards Agency (FSA) and Food Standards Scotland (FSS) now oversee such risk assessments in the UK.

[1] Criteria for Identifying Allergenic Foods of Public Health Importance Björkstén B, Crevel R, Hischenhuber C, Løvik M, Samuels F, Strobel S, Taylor SL, Wal JM, Ward R Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2008;51:42-52

[2] Application of Scientific Criteria to Food Allergens of Public Health Importance Chung YJ, Ronsmans S, Crevel RW, Houben GF, Rona RJ, Ward R, Baka A Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2012;64(2):315-323

[3] Codex General Standard for the Labelling of Prepackaged Foods, CODEX STAN 1-1985, last modified 2018 available at http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/codex-texts/list-standards/en/

[4] FARRP International Regulatory Chart Food allergen labelling https://farrp.unl.edu/IRChart

The need for consumers with food hypersensitivity to be able to avoid exposure to eliciting foods, by accessing information, has been recognised since the 1980s. Food labelling is thus of vital importance to anyone with a food allergy.

Regulation of food allergens used as ingredients in prepacked foods

The labelling of prepacked food must carry a list of ingredients. This is where information must be found about the allergens intentionally included in the food as ingredients. To avoid possible omission of crucial allergen information through derogations (such as certain compound ingredients or flavourings) food labelling legislation has been amended and updated to require all ingredients, additives, flavourings and processing aids containing major food allergens to be declared.

As mentioned, international agreement was reached, at Codex Alimentarius, on a list of 8 allergen food groups that must always be declared. Currently[1] (as of September 2021) these are:

- ‘Cereals containing gluten; i.e., wheat, rye, barley, oats, spelt or their hybridized strains and products of these;

- Crustacea and products of these;

- Eggs and egg products;

- Fish and fish products;

- Peanuts, soybeans and products of these;

- Milk and milk products (lactose included);

- Tree nuts and nut products; and

- Sulphite in concentrations of 10 mg/kg or more’.

This list was based on estimates that about 95% of food allergic populations may react to a limited number of food groups. However, consumption and sensitisation patterns around the world must also be considered. Gendel 2012 has compared international allergen regulation[2], and as previously mentioned, FARRP’s regularly updated list of international food allergen labelling requirements is useful.

The EU prioritises 14 food groups (see Appendix 2 for more details) and moreover requires that their presence must be emphasised in the list of ingredients, e.g. by a different typeface or in bold. Allergen labelling requirements for the UK and EU are laid out in Regulation (EU) 1169/2011 which has been implemented in UK law. The list of priority food groups is in Annex II[3]. This list also recognises labelling exemptions for named particular allergenic derivatives, for example if a processing method has been assessed as removing or denaturing allergenic proteins, making the derivative no longer allergenic.

FSA has produced guidance on allergen labelling for prepacked foods[4]. More recently declarations are also required for prepacked for direct sale (PPDS) foods. Allergens present as cross contaminants from cross contact in the supply chain (including harvesting, transporting, handling, processing, storage and distribution) are dealt with differently (see below).

It is important to bear in mind that allergic reactions can occur to foods not currently prioritised in labelling legislation. For example, UK Anaphylaxis Campaign collects information from its members about what allergens they are avoiding. Their members reported a need to avoid such foods as: kiwi, banana, and a range of legumes (e.g. peas, beans, chickpeas) and many others which are more common than some of those on the EU/UK regulated list of 14.

Regulation of food allergens used as ingredients in non-prepacked and catered foods

Allergen information must also be provided for non-prepacked and catered foods in the UK and EU [Regulation (EU) 1169/2011]. Since 2014, individual member state jurisdictions of the EU and the UK require or permit declaration of allergens for non-prepacked foods via different communication routes.

In the UK, a food business selling catered, ready-to-eat or otherwise non-prepacked food must display signage inviting customers to ask for allergen information directly from staff, whether face to face or by telephone. Such information has to be retained and made available on request for all foods, products and dishes throughout the business. In other jurisdictions, the information must be made available in written or printed form. It is vital that information is consistent across all sources: printed and online, displayed on tables and other signage within the business. It must be accessible at the point of choice and at the point of delivery or service, and should be accurate, consistent and verifiable.

[1] Codex Alimentarius General Standard for the Labelling of Prepackaged Foods CXS 1-1985 Adopted in 1985. Amended in 1991, 1999, 2001, 2003, 2005, 2008 and 2010. Revised in 2018.

[2] Gendel SM. Comparison of international food allergen labeling regulations. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2012 Jul 1;63(2):279-85. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0273230012000797?via%3Dihub

[3] Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers. Readers are advised to refer to The European Commission website EUR-Lex https://eur-lex.europa.eu/homepage.html and use the search function for the latest version

[4] FSA food allergen labelling guidance https://www.food.gov.uk/business-guidance/allergen-labelling-for-food-manufacturers and https://www.food.gov.uk/document/food-allergen-labelling-and-information...

Following the death of Natasha Ednan-Laperouse in 2016, from a PPDS sandwich unknown to her contained sesame, a review was undertaken to prevent future occurrences. It was agreed by UK government that PPDS products should carry a label with the name of the food, and a full ingredients declaration with any of the 14 allergens, required in EU Reg. 1169/2011 Annex II, to be emphasised on the ingredients list.

UK regulation of labelling requirements for PPDS has been updated, affecting foods such as sandwiches, which are made and packed on the premises, and then placed on display. Previously, such foods did not require full ingredient or allergen labelling, providing this information was retained and made available to the consumer on request. The amended law is enforceable from 1st October 2021. FSA have produced a suite of tools and guidance on the new PPDS labelling requirements[1].

Labelling requirements for bulk industrial business-to-business (B2B) supply and catering packs are subject to the derogation that, with certain exceptions[2], other legally required information (including allergen labelling), may be supplied in commercial documents referring to the foods, where it can be guaranteed that such relevant documents either accompany the food, were sent beforehand or are provided with the delivery. However, this derogation does not apply:

- where prepacked food is intended for the final consumer, but marketed at a stage prior to sale to the final consumer, and where sale to a mass caterer is not involved at that stage,

and

- where prepacked food is intended for supply to mass caterers for preparation, processing, splitting or cutting up[3].

[1] FSA guidance on allergen labelling for PPDS foods https://www.food.gov.uk/business-guidance/allergen-labelling-for-prepack... and https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/fsa-food-alle...

[2]The name of the food, the date of minimum durability or the ‘use by’ date, any special storage conditions and/or conditions of use, the name or business name and address of the food business operator and certain quantity weight labelling requirements [Weights and Measures (Packaged Food) Regulations 2006].

[3] Regulation 1169/2011 Article 8 (7)

Regulated allergens, and other allergenic foods used as ingredients, have to be labelled and the appropriate information communicated throughout the supply chain to the final consumer. However, there are circumstances, such as shared primary production, transport, storage, manufacturing, preparation, presentation and service environments, that may introduce the risk of the presence of a food allergen which is not an intended ingredient.

Measures intended to reduce this risk have been endorsed by a Codex Alimentarius Code of Practice[1] and include:

- correctly labelling all food ingredients in any form throughout the supply chain

- managing food packaging and labelling materials to remove the risk of incorrectly labelled products entering the market

- consistent adherence to the recipe/product specification

- identifying any possibility of a non-ingredient allergen getting into other food or dishes

- preventing allergen cross-contamination by segregation

- communicating the possibility of any remaining unintended allergen presence using Precautionary Allergen Labelling (PAL).

Effective allergen segregation may be achieved by:

- physical separation - by production area or kitchen workspace

- separation by time - producing one product or dish at a time

- covering, wrapping, or packing and labelling part-prepared or finished foods and products

- effective allergen removal through washing and cleaning

- timely control of spillages

- validation and verification of all cleaning processes.

Policies and procedures to support allergen segregation need to be implemented, embedded in staff training, assessed, reviewed and updated to ensure that they are effective. These principles apply throughout the food supply chain, from primary production to the final consumer. They also include the need to implement alerts in case of accidental mis-formulation or cross-contamination and the ability to recall products from distribution and sale and inform relevant consumers.

Unintended allergen presence may be particulate (pieces, grains, powder) or possibly homogenised, i.e. more evenly distributed throughout the material. Bakery products, for example, may carry the risk of grains and seeds transferred in ovens and via work overalls or equipment.

Clean-in-place (CIP) equipment for wet products may be designed and processes validated and verified to demonstrate allergen removal. Chocolate production is generally ill-suited to wet cleaning, due to microbiological risks and damage to the product, so cleaning may involve passing fat or waste chocolate down the production line. This may not be sufficient to remove particles of nut, grains, or milk, in liquid or powder form.

[1] Codex Alimentarius Code of practice on food allergen management for food business operators CXC 80-2020 http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=http...

Only 2 of the 14 UK/EU regulated food allergens have concentration limits for labelling purposes. Sulphur dioxide and sulphites at concentrations of more than 10 mg/kg, or 10 mg/litre (parts per million), must be highlighted as allergens. Suppliers of products intended to be ‘gluten free’ may only use this claim if the gluten content is 20 mg/kg (parts per million) or less.

‘Free from’ foods are manufactured for a particular market of people who need to avoid certain foods to protect their health, or who to choose to do as part of a personal dietary regime. They tend to use substitute ingredients, such as tapioca, rice or potato instead of gluten-containing flour (e.g. wheat), or soya, rice or coconut instead of milk. They are often more expensive than their standard equivalents, partly because these substitutes may simply cost more, but also because the allergen segregation required to make such claims involves laboratory batch testing of ingredients, before allowing them onto the production site, which carries additional costs.

Most supermarkets have ‘free from’ aisles or shelves to ensure that these products are easy to find. However, it is important that manufacturers and retailers ensure that their labelling style and text do not mislead high-risk food-allergic consumers and others buying their food. They may believe that foods sold as ‘free from’ will be guaranteed not to contain all or any food allergens, when in fact many substitute ingredients in these product ranges are recognised regulated allergens such as almond, hazelnut, soya, lupin, as well as coconut, pea, bean and buckwheat.

The assurance of ‘free from’ claims require a combination of strict supply standards to ensure all raw materials are free from the claimed allergen, and subject to the strictest storage, handling, production and packing controls, to ensure complete segregation, with no risk of any cross-contamination. The BRC/FDF Guidance on ‘Free-From’ Allergen Claims provides helpful advice[1].

Precautionary allergen labelling was first used in the UK in the mid-1990s on prepacked branded and ‘own brand’ products made for supermarkets. Initially, these covered the unintended presence of peanuts and different tree nuts, and then sesame, egg, milk and eventually cereals such as wheat. In 2001 the FSA commissioned research examining shopping for everyday prepacked foods with a nut or peanut allergy. https://allergyaction.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/AC-May-contain-report-maycontainreport.pdf

Consumer behaviour and PAL

One in ten of the warnings on products carrying precautionary allergen labelling was missed by consumers. It was recognised that such precautionary labelling needs to be adjacent to the ingredients list, legible, and conspicuous. Further research has also indicated that there are many styles and forms of wording for declaring unintended allergen presence, and different meanings and weightings are attributed to them by consumers.

Leading food manufacturers and retailers started to appreciate that the use of these warning labels was limiting food choices for a significant proportion of consumers, and those sharing their food, and continue to work to improve allergen controls to reduce the need for them and improve product choice. At the same time, consumers (and those health professionals advising them) had (and still have) very variable attitudes - in some cases following them and rigorously avoiding PAL labelled products, but in other cases paying little attention to them. Heeding, or failing to heed, such labelling is stressful, and choosing safe food has a significant impact on quality of life, and in some cases on food costs for consumers at risk and those buying their food.

There are significant gaps in consumer and health professional understanding, of the controls implemented in food businesses, and how and why such advisory labelling is used. Similarly, food industry scientists and technologists are keen to understand the challenges facing food allergic consumers, which foods they need to avoid, and the impact of living with this condition. The British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (a professional body for allergy health professionals) has engaged with the food industry to improve dialogue and understanding and has invited food industry experts in allergen management to speak at recent conferences. Researchers involved in consumer and patient research also contribute to the work of the IFST Scientific Committee and Food Regulatory Special Interest Group (SIG).

Current regulation of PAL

Precautionary allergen labelling is currently voluntary, though it could be argued that not alerting food allergic consumers to the potential unintended presence of a non-ingredient allergen might render that food unsafe and breach other regulations. UK and EU food law requires food business operators to undertake risk assessments [Article 5 of Regulation (EC) 852/2004)] and to sell safe food [Article 14 of Regulation (EC) 178/2002].

PAL is expressly allowed and widely used in Australia and New Zealand. In the UK, best practice guidance from the FSA and leading trade bodies indicates that the use of advisory ‘may contain’ labelling should be the last resort of a series of risk assessments. It should never be used as an alternative to effective allergen management (as part of GMP), as this may devalue the impact of such warnings, making consumers sceptical and endangering their health.

A standardised approach, whether voluntary or mandatory, which could be applied to any food or drink on the market, would provide consistency in food allergen risk communication. Many questions arise which would need to be addressed: which allergens would be included (all those on Annex II or others)?; would this regulation be achievable across jurisdictions, and from every manufacturer, retailer or wholesaler?; what would it cost?; how would it be communicated?; would a logo or symbol be practical or understood?; would it be effective in protecting all consumers at risk?; would it be adequate to prevent all symptoms?; how could such regulation be enforced and what analytical support would be required to do so?

There is pressure from consumers, and others, to implement the regulation of unintended allergen presence and PAL. This will require the above questions to be addressed. It will also increase demand for appropriate, accessible and affordable analytical methods, which can be applied with some consistency across different forms of food (matrices), as well as consensus about the proportion of consumers who may be protected.

How much is too much? Setting limits of allergen presence in foods in which it is unintended as an ingredient

Risk assessment in food allergy is multi-layered. Its sole purpose is to prevent consumers at risk from exposure to a food allergen which may cause them harm. This raises many questions about: which consumers; what kind of exposure; what kind of harm. The most challenging question which has preoccupied food scientists and technologists, clinicians, analysts, regulators and consumers for decades is ‘how much is too much?’

While low doses of allergenic foods clearly can present some risk to allergic consumers, the imposition of a zero-tolerance level for undeclared allergens in such foods may not be practical or achievable. Identifying allergen levels in foods which may be protective involves a number of approaches.

The application of principles used in toxicology has been considered in assessing the risk of unintended allergen presence in food which may be a hazard for a minority of consumers at risk but not for the general population. Similar examples where toxicology principles apply in food production include food additives, and contaminants such as metals, pesticides, veterinary residues as well as naturally occurring toxins such as mycotoxins (Walker and Wong, 2014).

Characterising the amount of allergenic foods which would present a risk to public health requires understanding of both the severity of any allergic reactions to that food and of the ‘dose-response’ pattern for the ‘at risk’ population. If a group of food allergic individuals (under clinical supervision) all consume a specific food allergen in the same form and in measured amounts, it is possible to plot the amounts of allergen which are known to have triggered symptoms to produce a ‘dose-response’ curve. These dose-response curves for individuals can then be combined into a population dataset and calculate a ‘minimum eliciting dose (ED), the minimum dose that elicits an effect in a defined proportion of the allergic population. For example, ED50 is the dose of an allergen that will cause a reaction in 50% of the population known to be at risk. ED05 and ED01 are the eliciting doses that would be expected to be protective of 95 % and 99 % of the allergic population respectively.

A minimum eliciting dose can be translated into a ’threshold’ or ‘action level’ - the concentration of an allergen in a product, above which risk management actions must be carried out to protect the at-risk population. In the case of food allergens, the risk management actions could be to apply PAL as a risk communication warning to at-risk consumers to avoid eating that product. Below this action level, PAL for example. may be considered unnecessary.

The Allergen Bureau Food Industry Guide to the Voluntary Incidental Trace Allergen Labelling (VITAL®) Programme Food_Industry_Guide_VITAL_Program_Version_April_2021_VF1.pdf (allergenbureau.net) is a standardised allergen risk assessment process for the food industry. It is widely used in Australia and New Zealand but has yet to gain widespread acceptance globally. The system is free to download (Version 3) and should be consulted in full, but important aspects include:

- precautionary labelling should only be used after a thorough assessment of the risk

- precautionary allergen labelling must NEVER be used as a substitute for good manufacturing practice (GMP) or as a generic disclaimer. Every attempt must be made to eliminate or minimise unintended presence by adhering to GMP

- the ONLY precautionary statement to be used in conjunction with VITAL® is: ‘may be present: name of allergen’.

A distinction can be made between two main approaches for risk assessment: Deterministic and Probabilistic. The former is a simple arithmetical method using reference minimum eliciting doses, food intake and allergen contamination data. The Allergen Bureau has established reference doses for 14 priority allergens[1] and the VITAL® system demonstrates how to carry out a deterministic risk assessment, using these data and the amount of food intake in a single eating occasion. In practice, there may be caution about using such an approach. ED01 is the eliciting dose in relation to an underlying risk that 1 in 100 allergic individuals will have a reaction. Discussions continue to find out if this balance of risk is acceptable and it may be tempting to opt for the analytical limit of detection as a default action limit, which may not bear any relation to true risk. It is also necessary to discuss the potential severity of any symptoms, considering recognised and other potential co-factors which may alter thresholds and/or severity. An ad hoc Joint FAO/WHO[2] Expert Consultation on Risk Assessment of Food Allergens in August 2021 published ED05 thresholds for nine allergens noting that ‘all symptoms up to ED05 fell into a mild or moderate category, while analysis of clinical data indicated that up to 5% of reactions at both ED01 and ED05 could be classed as anaphylaxis, although none were severe, based on the World Allergy Organisation definition. Furthermore, the Committee noted the extreme rarity of fatal food anaphylaxis (1 per 100000 person-years in the allergic population) and observed that no fatal reactions had been observed following exposure to doses at or below those considered for RfD (i.e. the ED01 and the ED05)’.[3]

A UK FSA funded study in adults with characterised peanut allergy[4] examined the effects of exercise and sleep deprivation on minimum eliciting doses of peanut protein. The findings included that the threshold of reactivity, in people with peanut allergy, significantly reduced with these factors putting them at greater risk of a reaction, if exposed to low levels of peanut. An allergic reaction is likely to be affected by other co-factors, e.g. infection, menstruation, alcohol, which may reduce allergen thresholds and/or increase reaction severity. Thus, it may be necessary to factor in the whole dose response curve, consumption patterns as a measure of exposure, and the percentage of the population who have the allergy. This is the probabilistic approach applied most extensively in the Integrated Approaches to Food Allergen and Allergy Management (iFAAM) study, https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/ifaam/, which developed tools and approaches for the food industry, and particularly to support small and medium-sized businesses (SME) in allergen management[5]. These include an allergen tracking tool that can estimate the probability of unintended allergen presence by identifying this presence, and then undertaking a vulnerability assessment based on the production steps and tiered risk assessments. These are described in a short e-seminar intended to familiarise the viewer with the concepts of food allergen risk assessment and specifically with the risks from unintended allergen presence[6].

The International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) has established an expert group on ‘Allergen Quantitative Risk Assessment (QRA): The Development and Integration of Methodology to Link Emerging Tools with Risk Management Actions across the Supply Chain, including Precautionary Labelling’. The aim is to systematise and provide best practice for the application of allergen QRA. The expert group report will be published in early 2022 https://ilsi.eu/scientific-activities/food-safety/food-allergy/.

[1] Allergen Bureau, 2019, Summary of the 2019 VITAL Scientific Expert Panel Recommendations, https://vital.allergenbureau.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/VSEP-2019-Summary-Recommendations_FINAL_Sept2019.pdf

[2] FAO/WHO: The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations and the World Health Organisation of the United Nations

[3] FAO/WHO ad hoc Joint Expert Consultation on Risk Assessment of Food Allergens http://www.fao.org/3/cb6388en/cb6388en.pdf

[4] FSA TRACE study https://www.food.gov.uk/news-alerts/news/peanut-allergies-affected-by-exercise-and-sleep-deprivation-new-study-finds

[5] Final Report, iFAAM, GA 312147, https://cordis.europa.eu/docs/results/312/312147/final1-ifaam-final-report-ver-6.pdf

[6] Ben Remington, E-Seminar: Introduction to food allergen risk assessment, Government Chemist, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/e-seminar-introduction-to-food-allergen-risk-assessment

In 2020 and 2021, FSA undertook research prioritisation exercises on food hypersensitivity research priorities. A UK-wide public consultation identified unanswered research questions and a series of stakeholder workshops resulted in 10 priority uncertainties in evidence, from which 16 research questions were developed. These were summarised under the following five themes[1],[2]:

- communication of allergens, both within the food supply chain and then to the end-consumer (ensuring trust in allergen communication)

- impact of socioeconomic factors on consumers with food hypersensitivity

- drivers of severe reactions

- mechanism(s) underlying loss of food hypersensitivity tolerance

- risks posed by novel allergens/processing.

Studies are already underway looking into early life dietary intervention (following the EAT Study outlined above) and food allergy in older children and adults, collecting National Health Service (NHS) and other data about severe and fatal reactions to foods in the UK - trigger foods, treatment and management, quality of life and additional costs associated with food hypersensitivity and allergy recalls https://www.food.gov.uk/research/food-allergy-and-intolerance-research.

Further research is underway to improve allergen analysis and reporting, to understand the role of regulation in protecting individuals with food hypersensitivity and to identify routes towards standardised and even regulated PAL.

[1] Turner, P and O’Brien, J, 2021, FSA Science Council Working Group 5 Review of the FSA’s research programme on food hypersensitivity Final Report, http://food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/fsa-21-06-09-annex-science-council-wg5-final-report.pdf

[2] Turner, P.J., Andoh-Kesson, E., Baker, S., Baracaia, A., Barfield, A., Barnett, J., Brunas, K., Chan, C.-H., Cochrane, S., Cowan, K., Feeney, M., Flanagan, S., Fox, A., George, L., Gowland, M.H., Heeley, C., Kimber, I., Knibb, R., Langford, K., Mackie, A., McLachlan, T., Regent, L., Ridd, M., Roberts, G., Rogers, A., Scadding, G., Stoneham, S., Thomson, D., Urwin, H., Venter, C., Walker, M., Ward, R., Yarham, R., Young, M. and O’Brien, J. (2021), Identifying key priorities for research to protect the consumer with food hypersensitivity: a UK Food Standards Agency Priority Setting Exercise, Clinical & Experimental Allergy, Accepted Author Manuscript, 2021; 00: 1– 9 https://doi.org/10.1111/cea.13983

Dr Paul Turner, member of the FSA Science Council https://science-council.food.gov.uk/, speaks about food hypersensitivity research https://food.blog.gov.uk/2020/09/22/the-food-allergy-and-intolerance-research-programme-dr-paul-turner/

Anagnostou, K., Islam, S., King, Y., Foley, L., Pasea, L., Bond, S., Palmer, C., Deighton, J., Ewan, P. and Clark, A., (2014). Assessing the efficacy of oral immunotherapy for the desensitisation of peanut allergy in children (STOP II): a phase 2 randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 383 (9925), pp. 1297-1304.

Nanoparticles show a talent for blocking immune reactions http://www.nature.com/news/2007/070702/full/news070702-16.html

Prescott, S.L., Pawankar, R., Allen, K.J., Campbell, D.E., Sinn, J.K., Fiocchi, A., Ebisawa, M., Sampson, H.A., Beyer, K. and Lee, B.W., (2013). A global survey of changing patterns of food allergy burden in children. World Allergy Organization Journal, 6 (21), pp. 1-12

Michael Walker and Hazel Gowland, 2017, Food Allergy: Managing Food Allergens’, in ‘Analysis of Food Toxins and Toxicants’, Eds. Yiu-Chung Wong & Richard J. Lewis, Wiley, ISBN: 978-1-118-99272-2, pp 711 – 742, http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-1118992725.html

Further reading

- Muraro, A., Hoffmann‐Sommergruber, K., Holzhauser, T., Poulsen, L.K., Gowland, M.H., Akdis, C.A., Mills, E.N.C., Papadopoulos, N., Roberts, G., Schnadt, S. and Ree, R. (2014) EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines. Protecting consumers with food allergies: understanding food consumption, meeting regulations and identifying unmet needs. Allergy 69, 1464–1472

- Crevel, R.W., Baumert, J.L., Baka, A., Houben, G.F., Knulst, A.C., Kruizinga, A.G., Luccioli, S., Taylor, S.L. and Madsen, C.B. (2014a) Development and evolution of risk assessment for food allergens. Food and Chemical Toxicology 67, 262–276

- Taylor, S.L., Baumert, J.L., Kruizinga, A.G., Remington, B.C., Crevel, R.W., Brooke-Taylor, S., Allen, K.J., of Australia, T.A.B. and Houben, G. (2014) Establishment of reference doses for residues of allergenic foods: report of the VITAL expert panel. Food and Chemical Toxicology 63, 9–17

- Allen, K.J., Remington, B.C., Baumert, J.L., Crevel, R.W., Houben, G.F., Brooke-Taylor, S., Kruizinga, A.G. and Taylor, S.L., (2014). Allergen reference doses for precautionary labeling (VITAL 2.0): clinical implications. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 133 (1), pp. 156–164

- For example, the British Retail Consortium (BRC) Global Standard for Food Safety, https://www.brcglobalstandards.com/

- Forensic investigation of a sabotage incident in a factory manufacturing nut free ready meal in the UK, Walker M J, In: J Hoorfar, Ed. Case Studies in food safety and authenticity, Woodhead Publishing 2012, pp288 - 295

- M. J. Walker, P. Colwell, S. Elahi, K. Gray and I. Lumley, Food Allergen Detection: A Literature Review 2004 – 2007, J. Assoc. Public Analysts, 2008, 36, 1-18

- A. Scharf, U. Kasel, G. Wichmann, and M. Besler, Performance of ELISA and PCR methods for the determination of allergens in food: an evaluation of six years of proficiency testing for soy (Glycine max L.) and wheat gluten (Triticum aestivum L.), J. Agric. Food Chem., 2013, 61, 10261-10272

- Török, Kitti, Lívia Hajas, Vanda Horváth, Eszter Schall, Zsuzsanna Bugyi, Sándor Kemény, and Sándor Tömösközi. "Identification of the factors affecting the analytical results of food allergen ELISA methods." European Food Research and Technology (2015): 1-10

- P. E. Johnson, N. M. Rigby, J. R. Dainty, A. R. Mackie, U. U. Immer, A. Rogers, P. Titchener, M. Shoji, A. Ryan, L. Mata et al., A multi-laboratory evaluation of a clinically-validated incurred quality control material for analysis of allergens in food, Food Chem., 2014, 148, 30-36

- M. Sykes, D. Anderson, and B. Parmar, Normalisation of data from allergens proficiency tests, Anal. Bioanal. Chem., 2012, 403, 3069-3076

- Muraro, A., Hoffmann‐Sommergruber, K., Holzhauser, T., Poulsen, L.K., Gowland, M.H., Akdis, C.A., Mills, E.N.C., Papadopoulos, N., Roberts, G., Schnadt, S. and Ree, R. (2014) EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines. Protecting consumers with food allergies: understanding food consumption, meeting regulations and identifying unmet needs. Allergy 69, 1464–1472

- Crevel, R.W., Baumert, J.L., Baka, A., Houben, G.F., Knulst, A.C., Kruizinga, A.G., Luccioli, S., Taylor, S.L. and Madsen, C.B. (2014a) Development and evolution of risk assessment for food allergens. Food and Chemical Toxicology 67, 262–276

- Taylor, S.L., Baumert, J.L., Kruizinga, A.G., Remington, B.C., Crevel, R.W., Brooke-Taylor, S., Allen, K.J., of Australia, T.A.B. and Houben, G. (2014) Establishment of reference doses for residues of allergenic foods: report of the VITAL expert panel. Food and Chemical Toxicology 63, 9–17

- Allen, K.J., Remington, B.C., Baumert, J.L., Crevel, R.W., Houben, G.F., Brooke-Taylor, S., Kruizinga, A.G. and Taylor, S.L., (2014). Allergen reference doses for precautionary labeling (VITAL 2.0): clinical implications. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 133 (1), pp. 156–164

- Walker, M.J. and Wong, Y.C. (2014) Protection of the Agri-Food Chain by Chemical Analysis: The European Context. In: Rajeev Bhat, Vicente M. Gomez-Lopez (Eds) Practical Food Safety: Contemporary Issues and Future Directions, Wiley-Blackwell, pp 125–144

- Walker, M.J., Burns, D.T., Elliott, C.T., Gowland, M.H. and Mills, E.C., 2016. Is food allergen analysis flawed? Health and supply chain risks and a proposed framework to address urgent analytical needs. Analyst, 141(1), pp.24-35

- How does dose impact on the severity of food-induced allergic reactions, and can this improve risk assessment for allergenic foods? Dubois AEJ, Turner PJ, Hourihane J, Ballmer-Weber B, Beyer K, Chan C-H, Gowland MH, O’Hagan S, Regent L, Remington B, Schnadt S, Stroheker T, Crevel RWR. Allergy January 2018 doi: 10.1111/all.13405

- Michael Walker and Hazel Gowland, 2017, Food Allergy: Managing Food Allergens’, in ‘Analysis of Food Toxins and Toxicants’, Eds. Yiu-Chung Wong & Richard J. Lewis, Wiley, ISBN: 978-1-118-99272-2, pp 711 – 742, http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-1118992725.html

- Walker M.J., Gowland, M.H., Points, J., Managing Food Allergens in the U.K. Retail Supply Chain. Journal of AOAC International VOL. 101, NO. 1, 2017 1

Institute of Food Science & Technology has authorised the publication of this updated Information Statement on Food Allergy.

The initial IFST Food Allergy Information Statement was prepared and updated by Professor J. Ralph Blanchfield in cooperation with IFST’s Scientific Committee. Following an interim review in September 2018, Dr Hazel Gowland FIFST and Dr Michael Walker FIFST completed this full revision mid-2021. They acknowledge the support of colleagues on IFST Scientific Committee and Natasha Medhurst (Scientific Affairs Manager).

This information statement is dated September 2021.

The Institute takes every possible care in compiling, preparing and issuing the information contained in IFST Information Statements, but can accept no liability whatsoever in connection with them. Nothing in them should be construed as absolving anyone from complying with legal requirements. They are provided for general information and guidance and to express expert professional interpretation an opinion, on important food-related issues.