October 2021

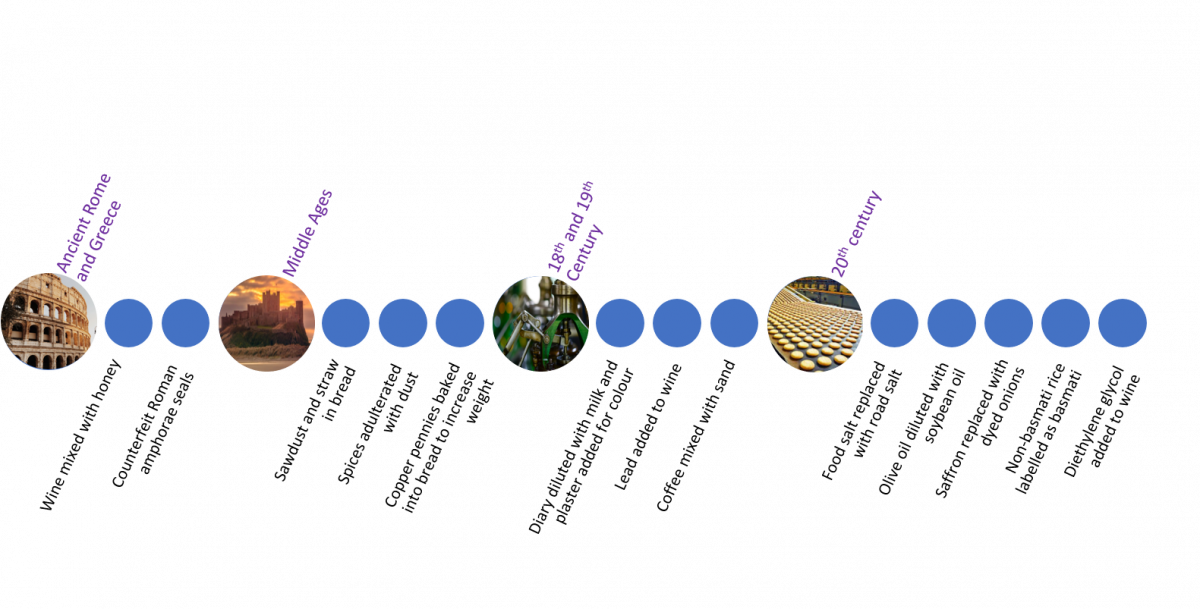

Food fraud has been conducted since ancient Greek and Roman times but is rapidly increasing due to the complex, global supply chain, pressure on suppliers to reduce prices and the possibility of large profits.

Food fraud has gained increasing recognition and concern since 2008 when milk and infant formulas were contaminated with melamine in China, followed by horsemeat being detected in products labelled as beef in Europe in 2013. Food fraud is typically motivated by profit, some forms can be harmful to consumers or mislead the purchaser/consumer as to the authenticity of the food or animal feed.

Food fraud is the:

- intentional substitution, addition or removal of a material to increase the perceived value of the material (ingredients, finished product or packaging) or reduce the cost of its production

- attempt to mask dilution through the addition or substitution of a material

- misrepresentation (e.g. stating a product is organic when it is not) and misleading or false statements.

It includes Economically Motivated Adulteration (EMA), stolen goods, grey market and counterfeiting3. It becomes ‘food crime’ when the fraudulent activity is no longer conducted by individual criminals, but by a group with the intent to deceive and harm businesses or consumers purchasing food products4.

There is a growing motivation to adulterate or counterfeit food by individuals or groups. Food and drink in the United Kingdom (UK) is more than a £225 billion industry1 and as food fraud can result in thousands of pounds of profit, from just one shipment of fraudulent food2, it can be a very profitable venture.

Food fraud, like food defence, is a part of the food protection ‘umbrella’. Both can be economically driven, however, the motivation behind food fraud is monetary gain, whereas the intent behind food defence is to cause harm through any form of intentional, malicious adulteration or economic disruption, and is typically ideologically motivated. Areas impacted by food defence programs include cyberattacks and sabotage.

|

|

Food defence |

Food fraud |

Food safety |

|

Illegal processing |

|

|

|

|

Sabotage (intentional contamination) |

|

|

|

|

Waste diversion |

|

|

|

|

Espionage |

|

|

|

|

Extortion |

|

|

|

|

Cybercrime |

|

|

|

|

Addition |

|

|

|

|

Substitution |

|

|

|

|

Dilution |

|

|

|

|

Counterfeiting |

|

|

|

|

Misrepresentation |

|

|

|

|

Grey market, theft |

|

|

|

|

Unintentional contamination (microbiological, physical, chemical, radiological) |

|

|

|

Food fraud has the potential to become a food safety issue if there is the potential for harm to consumers through:

- direct risk from exposure to toxic or lethal substances

- indirect risk from low-dosage exposure to a contaminant over a long period of time, or from using a product where the nutritional value has been reduced due to substitution or dilution5.

In 2008 milk was intentionally diluted and adulterated with melamine to increase the apparent protein content, due to the increased nitrogen content from melamine. In powdered infant formula made from the adulterated milk, melamine levels as high as 4,400 mg/kg were recorded6.

What started as a food fraud incident became a food safety issue when the infant milk formula was linked to urinary tract ailments (crystals and stones in the urine leading to kidney stones)7 resulting in the hospitalisation of nearly 52 thousand infants and 6 deaths8.

Incidents of food fraud have been recorded dating back into antiquity, with some examples being:

2020 - ketchup produced using unsafe, fake illegal products, with incorrect labelling and without the correct licence in Punjab, India9

2019 - traditional pig breeds used for the production of Parma and San Daniele hams were crossed with breeds that grow faster. The resulting higher water content did not meet the requirements of the Protected Designation of Origin (PDO)10

2018 - imported honey in Canada adulterated with foreign sugars11

2017 - aluminium foil used in place of edible silver leaf on sweetmeats in India12

2013 - food containing horsemeat were mislabelled as beef

2012 - vodka laced with methanol in Czech Republic13

2008 - milk and infant formula adulterated with melamine

2007 - pufferfish mislabelled as monkfish in California and Hawaii, USA14

2003 - insecticide mixed into group beef by a supermarket employee in Michigan, USA15

1985 - diethylene glycol added to wine in Austria to add desired sweetness.

Products most at risk of food fraud16

Olive oil |

Fish |

Organic foods |

Milk |

Grains |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Honey & maple syrup |

Coffee and tea |

Spices |

Wine |

Certain fruit juices |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Numerous factors contribute to food fraud, which can vary from country to country, the level of development and regulatory structure:

- Opportunity:

- inherent technical aspects of the products, such as the physical state of an ingredient or product (e.g. liquid versus powder); degree of processing (e.g. a herb as a whole plant is less vulnerable than dried leaves); whether there is an analytical testing method and the availability of the detection method; knowledge (e.g. diluting milk with water and replacing with melamine to increase the apparent protein content); complexity of composition (e.g. vanilla); non-food grade equivalent available; availability of technology

- technical measures such as product testing upon receipt, supplier approval programmes and functional performance of ingredients

- access by authorised employees, visitors, contractors or unauthorised people to products during the supply chain, for example during manufacture or storage

- number of times the product changes hand / or use of agents and brokers

- transparency of the supply chain

- differences in availability and demand17.

- Economic factors: including customer pressure to reduce prices, availability versus demand, supply shortage due to political unrest, increase in prices, austerity measures impacting regulatory agencies and trade barriers etc.

- Lack of control measures including:

- technical - food safety legislation, historical lack of testing for the adulterant (e.g. starch in food), inability to test (e.g. no analytical test) etc.

- managerial - lack of regulatory enforcement, food security, stable government, social/business acceptance (‘fraud doesn’t harm anyone’ attitude or ‘it won’t happen to us’), specifications/contracts etc.

- Complexity of supply chain: length, transparency, vertical integration, single ingredient source from approved supplier as opposed to open market etc.

- Insufficient supplier approval and performance programs: including on-site audits which includes a food fraud component, analytical testing and tracking of analytical results and complaints18

- History of food fraud: recurring fraud in the same product over a period of time, a pattern of food fraud in growing/manufacturing country and number of legitimate reported incidents can point to increased food fraud vulnerabilities.

A food fraud vulnerability plan documents the relevant assessment and mitigation measures developed by a cross-functional team. The elements of such a food defence plan includes the following:

- vulnerability assessment

- mitigation measures

- evaluation of mitigation measure effectiveness

- assessment and revision as necessary, e.g. following detection of food fraud at a manufacturing site, new food fraud in the industry, new detection method etc.

- reviewing the plan to ensure the mitigation measures implemented continue to be effective.

Food fraud vulnerability assessments and mitigation plans require a cross-functional approach across the whole organisation and a focus on prevention, rather than detection followed by a response19, 20.

Food fraud vulnerability assessment

Food fraud vulnerability assessments have similarities to Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) plans and should ensure that21,22,23:

- vulnerabilities are identified and the impact assessed. Consider:

- all activities of the business and a wide range of hazards

- where the vulnerable points in the supply chain are

- the complexity of the supply chain (number of countries, suppliers etc.)

- advances in technology that may allow a perpetrator to mask food fraud

- vulnerable points externally and internally (company-wide) e.g. purchasing, physical access, likelihood of successful food fraud, including direct suppliers and supply chain network, customers and employees

- difference between hazards, risks and vulnerability (exposure to a risk)

- severity and scale of harm that may be caused e.g. effect on consumer health of dilution of milk with water versus a toxic substance.

- corrective actions and preventative actions (mitigation strategies) are determined and prioritised

- it is reviewed and verified

- records are maintained.

Hazards to be considered should include as wide a range as possible, and may include:

- the use of fraudulent raw materials e.g. non-Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) packaging sold as real FSC, olive leaves in place of oregano, misdeclaration of country of origin of jasmine rice

- downgraded or substituted product e.g. basmati rice adulterated with cheaper varieties; tilapia instead of sea bass, waste for disposal recycled back into the supply chain, recycled paperboard sold as virgin board

- falsified or misleading packaging e.g. genuine brand logos obtained through deception and used on counterfeit products such as high vale wines

- undeclared intentionally added substances which are allergenic, for example, peanut products to cumin to increase volume

- fraudulent documents which falsely represent products as certified e.g. organic standards, sustainability endorsements or protected designation of origin (PDO) labels

- genuine product made in excess of purchasing contracts.

VACCP (Vulnerability Assessment and Critical Control Point) is a method used to assess and mitigate vulnerabilities from food fraud/authenticity and possible adulteration. The process is similar to HACCP and TACCP (Threat Assessment and Critical Control Point), although the latter is designed to protect against intentional adulteration for food defence purposes. TACCP can be linked with VACCP to identify threats and vulnerabilities.

Mitigation strategies should be implemented effectively to prevent or minimise vulnerabilities to food fraud. They must be specific to each company, manufacturing site and product.

To ensure the correct implementation of each mitigation strategy, companies should:

- monitor procedures and methods

- document the corrective actions to be taken if mitigation strategies are ineffective or not implemented correctly

- verify that monitoring is being conducted and corrective actions are being followed when appropriate.

Prevention of food fraud must be cross-functional (not just a food safety function issue) and implemented across businesses and supply chains22,24. Food fraud training of all departments, including Procurement and Operations is important to ensure:

- procuring supplies of products and ingredients from reputable, approved suppliers

- approval of source suppliers (site where the products are actually made), not just brokers and agents

- raw ingredient/finished product specifications are understood and include a full description of the product (e.g. botanical species, variety (such as Cinnamomum verum vs. Cinnammum cassia) and all ingredients including key attributes

- procedures in place for products that do not meet the approved specification or are not legally compliant

- use of a recognised statistical sampling programme for sampling and inspection on receipt, which is appropriate for the raw ingredient and consistently applied

- the testing laboratory is appropriately accredited for the analysis required

- request Certificates of Analysis for relevant criteria, such as active ingredient content and method used e.g. piperine for pepper

- known harvest cycle as this can influence availability of products and quality

- verification of authenticity of ingredients used in food manufacturing

- development, implementation and effective testing programmes for materials identified as being highly vulnerable to food fraud

- maintenance of equipment, such as weighing scales and ensure an effective calibration programme is in place

- reviews of costs and benefits of conducting on-site audits, especially for high-risk suppliers

- request suppliers of vulnerable products to conduct a mass balance exercise (typically as part of the traceability programme) to prove ability to account for all quantities of raw ingredients, products and packaging

- review and implementation of anti-counterfeit technologies where appropriate23

- follow correct importation rules; good manufacturing practice (GMP) and industry standards are applied

- knowledge of food laws where the products and ingredients are manufactured and sold, to avoid unintended non-compliance to legal requirements

- alerting authorities to cases of suspected food crime, e.g. Food Standards Agency (FSA) and Food Standards Scotland (FSS): FSA's National Food Crime Unit, Scottish Food Crime Hotline

The food supply chain is complex which challenges the capabilities of analytical tools. Testing methods are usually targeted at the expected type of fraud, e.g. sugar added to honey, and only allow for a ‘snapshot in time’.

Current technologies for food fraud detection include:

- species identification (meat, fish, plant) - Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) using DNA sequencing, PCR testing, gel electrophoresis, GMO detection and quantification

- ion chromatography e.g. sugar substitutes

- Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (IRMS) fingerprints (measurement of stable isotopes) to confirm regional or process specific foods (geographical, fertilisation process, fraud e.g. watering down wines)

- Rapid Evaporative Ionisation Mass Spectrometry (REIMS) that allows the characterisation of food without requiring sample preparation25

- ELISA method e.g. soya flour addition, peanuts in cumin

- Near-infrared spectroscopy allows the measurement of large quantities of materials at once, to provide a physicochemical fingerprint of a sample

- X-ray spectroscopy

- mass spectrometry

- chromatography (liquid and gas)

- wet chemistry such as Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) or one of the Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) variants

Examples:

- on receipt, a raw ingredient does not look typical or has an odd smell/texture

- there is a shortage of raw ingredients (due to natural disasters, political unrest, crop failures etc.) and there has not been an anticipated price change (e.g. cumin in India contaminated with peanut shells)

- excess raw ingredient availability, without an increase in the number of growing locations

- a supplier is selling materials below market price

- demands are made of the supplier to significantly reduce costs

- a raw material is sourced from an atypical growing climate or country

- allergens or bacteria are detected that are not typical of the product

- PAS 96:2017 Guide to protecting and defending food and drink from deliberate attack https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/pas962017.pdf

- Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed portal https://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/rasff_en

- Counter fraud good practice for food and drink businesses, Chartered Institute of Environmental Health https://www.foodstandards.gov.scot/downloads/Counter_Fraud_Good_Practice_Guide_-_FSA_and_FSS_-_Nov_2016.pdf

- Site Security & Food Defence Awareness eLearning from Techni-K (free for manufacturing sites) https://techni-k.co.uk/product-defence/

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Food Defense Plan Builder https://www.fda.gov/food/food-defense-tools-educational-materials/food-defense-plan-builder

- Food Fraud Intention, detection and management. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Bangkok, 2021. http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cb2863en/

- PwC/SSAFE Food fraud vulnerability assessment: https://www.pwc.com/sg/en/industries/assets/food-fraud-vulnerability-ass...

- Trello Food Fraud Risk Information https://trello.com/b/aoFO1UEf/food-fraud-risk-information

- Subscription-based: Decernis; Fera HorizonScan; FoodShield Food Adulteration Incidents Registry (FAIR)

References

- Statistics published by the Office of National Statistics and the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs: Food Statistics Pocketbook Summary https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/food-statistics-pocketbook/food-statistics-in-your-pocket-summary

- Food Control, Volume 71, January 2017, Pages 358-364, The economics of a food fraud incident – Case studies and examples including Melamine in Wheat Gluten. Douglas C., Moyera Jonathan, W.DeVriesb, John Spink. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.07.015)

- GFSI, Tackling Food Fraud Through Food Safety Management Systems. https://mygfsi.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Food-Fraud-GFSI-Technical-Document.pdf.

- HM Government. Elliott Review into the Integrity and Assurance of Food Supply Networks – Final Report, July 2014 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/350726/elliot-review-final-report-july2014.pdf

- US Government Accountability Office. Food and Drug Administration Better Coordination Could Enhance Efforts to Address Economic Adulteration and Protect the Public Health. October 2011. https://www.gao.gov/new.items/d1246.pdf

- Toxicological and health aspects of melamine and cyanuric acid: report of a WHO expert meeting in collaboration with FAO, supported by Health Canada, Ottawa, Canada, 1–4 December 2008. https://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/chem/Melamine_report09.pdf

- Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Units, Melamine: Information for Pediatric Health Professionals. https://www.pehsu.net/_Library/facts/melamine_factsheet.pdf).,

- Quality regulation and competition in China’s milk industry, June 2015, Custos e Agronegocio 11(1):128-141, Chan Wang, Youhua Chen, X.-G. He)

- https://www.newfoodmagazine.com/news/103845/punjab-food-authority-stops-production-of-fraudulent-ketchup-factory/

- (https://www.inspection.gc.ca/about-the-cfia/science-and-research/our-research-and-publications/report/eng/1557531883418/1557531883647)

- https://trello.com/c/ozENYG8Z/271-confectionery

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/BT-CO-20120916-700862

- it.org/7993/20170112162923/http://www.fda.gov/Safety/Recalls/ArchiveRecalls/2007/ucm112204.htm

- https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5218a3.htm

- 4.12.2013. Report on the food crisis, fraud in the food chain and the control thereof (2013/2091(INI)). Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//NONSGML+REPORT+A7-2013-0434+0+DOC+PDF+V0//EN

- Manning, L. and Soon, J.M. (2016), Food Safety, Food Fraud, and Food Defense: A Fast-Evolving Literature. Journal of Food Science, 81: R823-R834. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.13256)

- Appendix XVII: Guidance on Food Fraud Mitigation The U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention’s (USP’s) Expert Panel on Food Ingredients Intentional Adulterants.

- Trends in Food Science & Technology. Volume 62, April 2017, Pages 215-220.

- Food fraud prevention shifts the food risk focus to vulnerability., David L. Ortega, Chen Chen, Felicia Wu

- Food Control. Volume 105, November 2019, Pages 233-241.

- Introducing the Food Fraud Prevention Cycle (FFPC): A dynamic information management and strategic roadmap. John Spink, Weina Chen, Guangtao Zhang, Cheri Speier-Pero. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.06.002

- Food fraud vulnerability and its key factors. Trends in Food Science & Technology, ISSN: 0924-2244, Vol: 67, Page: 70-75. 2017. Saskia M. van Ruth, Wim Huisman, Pieternel A.Luning

- The ‘new’ phenomenon of criminal fraud in the food supply chain, 4 September 2014. NSF International. https://www.nsf.org/newsroom/whitepaper-the-new-phenomenon-of-criminal-fraud-in-the-food-supply-chain)

- CFIA Chronicle 360. https://www.inspection.gc.ca/chronicle-360/food-safety/food-fraud/eng/1508953954414/1508953954796

- Rapid Evaporative Ionisation Mass Spectrometry (REIMS) for Food Authenticity testing. Assuring the integrity of the food chain: Fighting food fraud (FOODINTEGRITY 2016) Simon Hird, Sara Stead, Julia Balog, Steven Pringle, Zoltan Takats

Institute of Food Science & Technology has authorised the publication of the following Information Statement on Food Fraud.

This is an update to the Information Statement that has been prepared by Julie Ashmore FIFST. It has been peer-reviewed and approved by the IFST Scientific Committee and is dated October 2021.

The Institute takes every possible care in compiling, preparing and issuing the information contained in IFST Information Statements, but can accept no liability whatsoever in connection with them. Nothing in them should be construed as absolving anyone from complying with legal requirements. They are provided for general information and guidance and to express expert professional interpretation and opinion, on important food-related issues.